Lessons from the Case: Andy Warhol Foundation v. Lynn Goldsmith (2021)

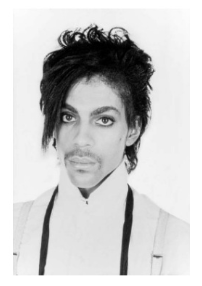

In 1981, when the artist known as Prince was an upcoming artist, photographer Lynn Goldsmith had a brief studio session with him and took some photographs of him which she never published.

In 1984 Goldsmith licensed the photographs to Vanity Fair magazine for use as an artist reference which meant that an artist would create a work of art based on the reference photograph. The license permitted Vanity Fair to publish an illustration based on theGoldsmith Photograph in its November 1984 issue, once as a full page and once as a quarter page. The license was a single use license on limited terms. The license further required that the illustration be accompanied by an attribution to Goldsmith. Warhol was commissioned to create an image of Prince for Vanity Fair. In addition to the image he created for the Vanity Fair article, Warhol went ahead and created 15 additional images to form what was collectively known as the Prince Series.

The Andy Warhol Foundation (AWF), which became the successors in title to Andy Warhol after his death in 1987, dealt with the Series, assigning ownership in some of the images and licensing others.

When Prince died in April 2016, Condé Nast (Vanity Fair’s parent company) reached out to AWF to license images from the Prince Series and used them for a tribute to Prince in May of 2016. This time, Goldsmith received no credit or attribution for the image. Sole credit was given to AWF instead. Only then did Goldsmith become aware of the Prince Series and in July 2016, she contacted AWF about her perceived infringement of her copyright. Goldsmith then registered her copyright in the image, and as a preemptive strike, AWF filed a suit in the United States District Court for Southern District of New York against Goldsmith for a declaratory judgment of non-infringement, or, in the alternative, Fair Use. Goldsmith countersued for copyright infringement.

At first instance, AWF got the upper hand, with the District Court finding for fair-use in favour of AWF based on their finding that the Prince Series was a transformative work. Goldsmith appealed, as expected.

On appeal to the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, the Second Circuit considered the four factors of the US Fair Use doctrine, which are:

- the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

- the nature of the copyrighted work;

- the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

- the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The Second Circuit found in favour of Goldsmith on all four factors.

Key to me from the Second Circuit’s ruling is the distinction between a derivative work and a transformative work. While the District Court concluded that Warhol’s work was transformative because it transformed Goldsmith’s image of Prince as “not a comfortable person” and a “vulnerable human being,” to an image of Prince as an “iconic, larger-than-life figure,” the Second Circuit disagreed with that finding.

The distinction between a derivative work and a transformative work is important because while one may pass as excusable fair use not infringing on the copyright of the primary work’s owner, the other does not. Derivative works, which present the same material in a new form without adding something new, require permission from the primary work to avoid infringement. Although derivative works involve some transformation of the primary work, they are excluded from the scope of fair use. An example of a derivative work would be a film based on a novel. The novel is the source/primary work and the screenplay and film are derivatives of the novel, which would require the permission of the primary work’s copyright owner.

In considering fair use, transformative works do something further than derivative works. Transformative works convey a new message or meaning entirely different from the primary work. They bear a new artistic purpose and character such that they stand apart from the primary work used to create them. A transformative work changes the primary work and gives it a new meaning, message, or expression. Examples of transformative works are works that use the primary work for “criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship,… research,” (as enumerated in US copyright law) or parody. These allowable uses are also reflected in the second schedule of the Nigerian Copyright Act.

In this case, in conclusion about the transformative nature of Warhol’s work, the Second Circuit stated, “Although we do not hold that the primary work must be ‘barely recognizable’ within the secondary work, … the secondary work’s transformative purpose and character must, at a bare minimum, comprise something more than the imposition of another artist’s style on the primary work such that the secondary work remains both recognizably deriving from, and retaining the essential elements of, its source material.”

Allowable uses of copyright work provide for the balance between the monopolistic rights of the copyright owner to control the use of their work on the one hand, and the benefit to society of the allowable use on the other.

For creators who are inspired to create works based on existing works, it is important to know the difference between a derivative work and a transformative work, which may be allowable without the permission of the copyright owner.