LAW

Are Architects’ Drawings Protected by Copyright?

My home in Lagos, Nigeria is an old civil service home. Four or five decades ago, all the houses on my street were identical, semi-detached, three-bedroom duplexes on plots of land demarcated by mango trees. A few years ago the street, like many other old residential areas in Lagos started changing. The Federal Government sold off its properties, which new owners converted to different purposes.

On my street, Lagos State leveled all the houses on their side of the street and put up a mid-income housing development. A mini estate of sorts. Where there had been about ten single family homes, we now had an estate of about 36 flats. Talk about getting the most out of your land. Some had knocked down their homes to create new structures, and others like my neighbour kept the bones of their building and added spectacular structures around it.

Naturally, I also wanted to do something new with my house. The house needed an update. An extra bedroom, maybe. Where would the extra bedroom go? An additional bathroom would be nice as well. Oh, and that extra, special living room that some people need for some reason. It’s the room where special guests are ushered into to talk serious business, make deals, exchange cash. Who knows? That’s what I imagine. The “adult room.”

Well, I didn’t quite know what I was going to do with my house. Plus, I had to be mindful of my pocket. I watched as people around me renovated, remodelled, added and subtracted from their homes. I had wild dreams. An architect friend of mine had done some drawings for me. But my bank account brought me back to reality. I didn’t have the money to do anything elaborate. And, I liked the character of the house the way it was. I liked the hardwood floors, the large windows, and the airy terrace in front. I liked being the only “old” house on the street. A reminder of what the houses on the street looked like. Some owners on the street had converted their houses to commercial properties, others had placed those crazy high “A” looking roofs on their houses. Almost all of them had closed off their terraces. None of those designs spoke to me.

Then I went to visit a friend in her home in Port Harcourt and found that the floor plan for her house was exactly the same as mine in Lagos. Just a little smaller. She had updated and added an extension, but she had kept all the elements of the original design that I liked. Finally, I had found the inspiration I was looking for. And best of all, it wouldn’t cost me a kidney to afford it.

So, on a visit with one of my uncles in Lagos, I was very excited to share my fascination over finding a house in Port Harcourt with the exact floor plan as mine in Lagos. My uncle also lives in an old colonial administration house in Lagos, which he has kept in its original design.

Anyway, we got talking about the house in Port Harcourt and how I was surprised to see another house built exactly like mine, just on a smaller scale.

And he said, “Yes, those are probably Cappa (Cappa and D’Alberto) homes. In those days, if you tried to copy their designs, Cappa would have you in court so fast your head would spin.”

Woah! What? Wait a hot second.

Yes, I know that Nigerian copyright law, past and present, protects works of architecture, and I’ve heard architects complain about their works being copied. I’d just never met any architect who went a step further than complaining to enforce their copyright in court. Very few things get me excited like when I hear about a business enforcing their legal rights.

Are Architects’ Drawings Copyrighted?

Wow! It took this long story to get to the point. Are architects’ drawings copyrighted? The short answer is yes.

The Nigerian Copyright Act protects works of architecture in the form of buildings and models. The Law states in Section 5(3), “Copyright in a work of architecture shall also include the exclusive right to control the erection of any building which reproduces the whole or a substantial part of the work either in its original form or in any form recognisably derived from the original, but not the right to control the reconstruction in the same style as the original of a building to which the copyright relates.”

U.S. Copyright law equally protects architectural works. The U.S. Copyright Act defines an architectural work as, “the design of a building as embodied in any tangible medium of expression, including a building, architectural plans, or drawings. The work includes the overall form as well as the arrangement and composition of spaces and elements in the design, but does not include individual standard features.”

Section 120 of the U.S. Copyright Act lays out the scope of exclusive rights in architectural works:

(a) Pictorial Representations Permitted.—The copyright in an ar- chitectural work that has been constructed does not include the right to prevent the making, distributing, or public display of pictures, paintings, photographs, or other pictorial representations of the work, if the building in which the work is embodied is located in or ordinarily visible from a public place.

(b) Alterations to and Destruction of Buildings.—Notwithstanding the provisions of section 106(2), the owners of a building embodying an archi- tectural work may, without the consent of the author or copyright owner of the architectural work, make or authorize the making of alterations to such building, and destroy or authorize the destruction of such building.

How Can an Architect Claim Copyright Infringement?

Like any other copyright protected work, the owner of an original protected architectural work can make a claim for copyright infringement against any person who interferes with the exclusive rights of the owner.

In a recent U.S. Court of Appeals (8th Circuit) case, Designworks Homes, Inc. v. Thomson Sailors Homes, LLC, No. 19-3458 (8th Cir. 2021), the court had to answer the copyright question between two groups of architects and home builders.

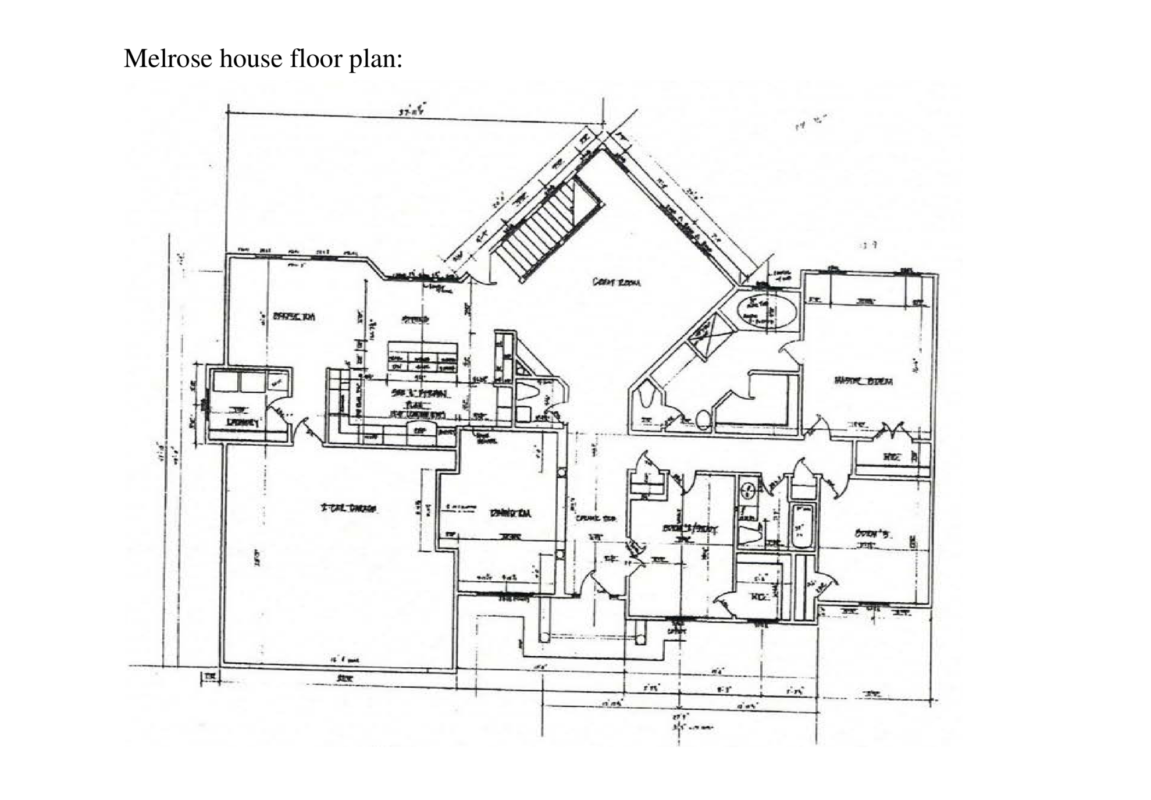

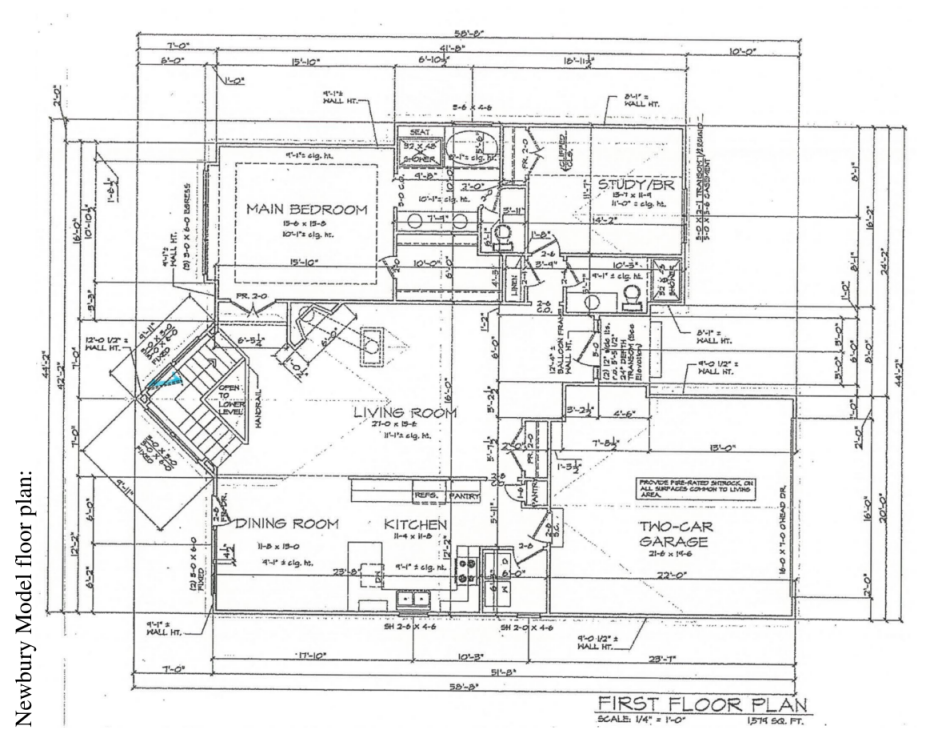

Designworks Homes, Inc. (Designworks) believed that Thomson Sailors Homes, LLC. (TSH) had copied Designworks’ Melrose Home “triangular atrium” design in their Newbury Model homes. According to Designworks, everyone involved in designing and promoting the Newbury Model (including displays in promotional materials) infringed on its copyright. The District Court disagreed with Designworks and found no substantial similarity between the two works. So Designworks appealed.

There are two elements to prove in any copyright infringement claim in the US.

- Ownership of a valid copyright. Designworks had a valid certificate of registration for the design so this was not an issue.

- Copying of the elements of the work that are original. Copying can be proven in two ways: (i) that the defendant had access to the copyrighted work (Designworks did not provide any evidence that TSH or any of the other parties had access to the Melrose Home) or (ii) substantial similarity of protectable material in the two works.

How Will a Court Assess Substantial Similarity in Two Copyrighted Works?

To assess substantial similarity in two copyrighted works, the court must determine whether in the eyes of the average lay person, the allegedly infringing work is substantially similar to the protectable expression in the copyrighted work. Would an ordinary, reasonable person look at the two works and think, “Yeah, those two are substantially similar”? (Raised eyebrows)

The court will also look at the total concept and feel of the works and try to distinguish between a work’s non-protectable elements and focus only on whether its protectable elements are substantially similar.

You can’t automatically infer that there was copying simply because there’s an element (in this case, a triangular atrium) occurring in both works.

In this case the Court of Appeal agreed with the District Court. Nothing to see here, there’s no substantial similarity between the two works! Quoting Judge Stras on the substantial similarity point:

“So even if one feature of both designs is a triangular atrium, there are plenty of differences, from the size of the atriums themselves to how they are integrated with the rest of the house, with each having rooms and stairways of differing shapes, sizes, and orientations.

“To an “ordinary, reasonable person” viewing both designs, “the total concept and feel of the” homes would not appear “substantially similar.” Hartman, 833 F.2d at 120–21; see also Taylor Corp., 403 F.3d at 966 (explaining that the focus should be on “the work[] taken as a whole”). In summary-judgment terms, our conclusion is the same as the district court’s: “the works are so dissimilar that ‘reasonable minds could not differ as to the absence of substantial similarity in expression.’” Hartman, 833 F.2d at 120 (emphasis added) (quoting Litchfield v. Spielberg, 736 F.2d 1352, 1355–56 (9th Cir. 1984)).”

The courts were not too happy with Designworks in this case. Designworks lost their claim and had to pay TSH’s full costs and attorney’s fees. Bad market!

Take a look at the two designs again and tell me what you think. Are they substantially similar or was this (as the District Court inferred) just Designworks trying to strong-arm another company to get a settlement out of them? Let me know what you think.

If you’d like a basic overview of copyright, click here to read the my article, The Basics: What is Copyright?